Miscellaneous Stories and Anecdotes

Some Overload!

John S. Brownlie, in his book ‘Railway Steam Cranes’, relates that a Craven Brothers crane of 1907 build (which would make it a 20 or 25 tonner, both being to the same basic design) was called upon one night to assist at a steelworks. Its task was to lift a steel ingot which had fallen through the floor of a wagon, so as to allow a replacement wagon to be run underneath. Great difficulty was experienced in lifting, even under full steam, however the task was completed and the crane returned to depot.

Details of the lift were sought the next day so as to charge for the work, at which time it was discovered that the ingot weighed in the region of 50 tons!

Disaster at Griseburn

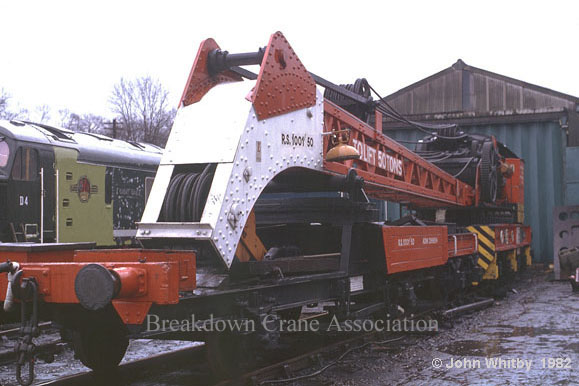

Cowans Sheldon RS1001/50, built for the LMS in 1930, was in the charge of Kingmoor (Carlisle) depot from 1936 to 1962. On 29th November 1948, it was awaiting return to depot, having dealt with a derailed wagon and brake van at Griseburn Ballast Sidings, when it itself became the subject of an accident of the crane crew’s own making, this accident having far graver consequences than the one to which it had been called to attend. Griseburn Ballast Sidings were located just north of Griseburn Viaduct, roughly midway between Settle and Carlisle.

RS1001/50 in preservation at the Midland Railway Centre

The breakdown train arrived at the scene of the derailment at 35 minutes past midnight and the re-railing operations were commenced without delay. The man in charge of the operation, Leading Fitter George Campbell, instructed that the crane be scotched prior to the rest of the breakdown train (comprising a travelling coach and three vans) being detached and moved clear, and a wedge-shaped wooden scotch was placed to either side of one of the wheels.

No instruction appears to have been given to apply the brakes on the crane carriage and jib runner, despite Campbell being fully aware of the steepness of the gradient. So this crane, of 104 tons in weight, was reliant on just one wooden scotch to hold it against unwitting travel down the 1-in-100 gradient upon which it was standing!

A little after 2.30 a.m. that same morning, the re-railing operations having been completed, train guard Alfred Cook was asked to bring the train close to the crane so as to minimise delay when they were ready to couple up. Cook was short on experience and twice started and stopped the train in its move of less than 400 yards down the gradient. It was still 100 yards short so he tried again, but this time the train made heavy contact with the jib runner and the crane was forced over the scotch. The scotch then became dislodged and the crane, with jib trailing, started to run away on the almost continuously falling gradient towards Carlisle.

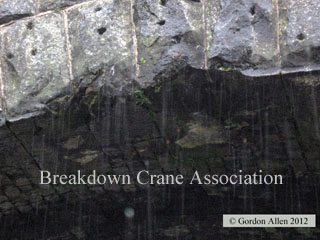

The jib of the crane had been in the process of being lowered at the time of the impact and was still about two feet above the jib runner as the crane ran away. A short distance down the line, the sheaves near the head of the jib hit an overbridge at 'Crow Hill' and shattered, the debris hitting and killing George Campbell as he stood on one of the jib runner's brake levers in an effort to slow or stop the crane (there were two brake levers, one each side of the runner, each braking the wheels on that side only). His effort would have been in vain anyway, since a braked jib runner of less than 10 tons tare would not have had much effect on the movement of over 100 tons of crane on a gradient.

Fitter Charles Campbell was making his way to the crane cab with the intention of fully lowering the jib when he was thrown off, breaking his thigh. The third member of the breakdown crew, crane driver T S Baty, was also thrown off, though not seriously injured.

Attempts had been made to halt the crane by placing objects on the line and between the spokes of the wheels, to no avail, and Cook had attempted to apply the handbrake on the crane carriage but he turned the handwheel the wrong way (it was later found to be fully ‘off’). Cook’s error is not surprising since the small brass ‘on/off’ plate was probably illegible in the dark and the handwheels on either side of the carriage were on a common shaft and hence turned in opposite directions to one another.

The crane ran down the falling gradient for 23 miles to beyond Lazonby where a slightly rising gradient, practically the last one before Carlisle, brought it to rest. Word had reached Carlisle about the runaway and they had prepared for it to run through if necessary. They had also considered intercepting it with an engine but decided that this would be too hazardous in the dark.

The Enquiry Officer concluded that it had been common practice for the crane crew to rely upon scotches rather than brakes and he recommended that brakes be used at all times, supplemented with scotches when necessary. He also recommended better identification of the handbrake wheels and their direction of turning, and the provision of rail slippers rather than wooden scotches. He also advised that the uncertainty concerning who is responsible for ensuring that the brakes are applied should also be attended to (i.e. train guard or crane foreman).

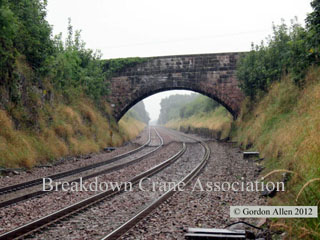

These pictures show clearly the steepness of the falling gradient and the damage to Crow Hill bridge. They are a reminder as to how a casual attitude to matters of safety can have horrendous consequences.

Crane Falls Over at Hixon

In January 1968, a 120-ton electric transformer was being transported on a short road journey from English Electric’s works at Stafford to a disused airfield at Hixon where the company’s abnormal loads were held pending onward transfer. Difficulties were experienced as the transporter and its load was being taken over an automatic half-barrier level crossing because the trailer needed raising to clear the ground but contact with overhead lines had to be avoided.

Whilst the transporter was astride the line, the crossing’s warning bells and lights activated and the barrier came down onto the transformer. Barely 30 seconds later the transporter was hit by a 12-coach express train, resulting in the deaths of eleven people on the train.

Reports of that tragic Hixon accident abound, however a comparatively minor incident that occurred in the clearing up operation is rarely told, specifically the overturning of Derby’s 75-ton Cowans Sheldon crane RS1092/75 and the circumstances that led to this:

The transformer involved in the collision was being cut into manageable pieces when the insulation caught fire, to be doused by the fire brigade with liberal quantities of water. There followed a sharp drop in the ambient temperature, causing the water that had soaked into the ground to freeze.

Temporary tracks were laid over this ground to give access to breakdown cranes, however a rise in temperatures led to thawing of the ground which subsided under the weight of the Derby crane as it was tandem-lifting a coach with Crewe’s 50-ton Cowans Sheldon crane RS1005/50. The Derby crane fell over but the driver was unhurt, though an inspector on the footplate jumped and broke a leg. One time crane supervisor Allan Baker believes that an unknown land drain under one of the supporting girders also played a part.

Letter of Approval for GWR No. 2 to lift 50 Tons

A letter from 1925 has come to light concerning the ability of the 36-ton Ransomes & Rapier breakdown crane GWR No. 2 to lift 50 tons on occasion. It is not apparent to whom the letter was addressed but it is signed by W A Stanier on behalf of C B Collett (Stanier was Principal Assistant to CME Charles Collett from 1922 to 1931). The letter is transcribed below:-

Mon. March 16th 1925

Dear Sir,

Capacity of 36 ton steam crane to lift up to 50 tons.

With reference to my conversation with Foreman Robson on Saturday last, I have this matter in hand with the makers, Messrs. Ransomes & Rapier, as to the capability of our crane No.2 lifting loads up to 50 tons, and for your information give below extract from their quotations.

"We have not included for strengthening any parts of the crane to suit the 50 ton occasional load which we consider can be applied with comparative safety as the crane in question was tested with 45 tons at 21'4" radius on a 16' base. We have therefore only allowed for the extra counterbalance and attachments for same to render the crane suitable for 50 tons at 20ft. on a 5'6" base on one side of the crane, as shown in Drawing No. 11364/22348.

"We would point out that the crane would not be stable on its wheels with the extra counterbalance attached, as the extra tail weight which the crane will take, and still be stable on its wheels, is only about 2½ tons. We are therefore including for an instruction plate to be as indicated on Drawing No. 10362.

"With regard to the duty of 50 ton occasional loads, we have assumed that this will be in accordance with your drawing No. 30/32 with the base of 5'6" on one side of the crane, but if you are only requiring our crane to lift the 50 ton load under normal conditions, i.e. 16'0" base, 8'0" per side, we beg to state that our crane will be quite suitable for this without any alteration or additional counterbalance."

You will note that this crane is allowed to lift 50 ton loads occasionally at 20ft. radius, and no alteration is contemplated to enable a 5'6" propping base on one side of the crane as the firm suggested, as we should generally be able to use the present 16ft. propping base, i.e. 8ft. on each side.

Yours truly,

for C.B.Collett,

(Signed) W.A.Stanier

John S. Brownlie B.Sc.(Eng.) 1921-1989

A Memorial Note

John Stewart Brownlie was author of the first of only two definitive histories of the British steam breakdown crane, namely: "Railway Steam Cranes - A Survey of Progress since 1875". This seminal work covers a history of the makers, descriptions of leading types, their operation and their technology. It was published privately in 1973 following an unsuccessful attempt to find a commercial publisher. With its low print run, the book which he sold for £3 apiece can now fetch up to £60.

John Brownlie aged 10, in 1931.

John Brownlie was born and brought up in Dennistoun, a district in the east end of Glasgow, where his father owned a cycle repair shop. Graduating from the Royal College of Science and Technology (now the University of Strathclyde), he was a member of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland, and worked for many years with James Howden & Co, the Glasgow makers of marine and power station machinery.

He received several inheritances, thus was financially independent, so took an early retirement at about 50 years of age following the death of his mother, whom he had lived with at 3 Murray Avenue, Kilsyth. He then moved to 71 Kingston Road where he died from a heart attack on 28th November 1989 at age 68 (the death certificate gives his name as "Brownlee"). Prior to his death he had been researching the history of the municipal gasworks of Scotland, and also planned to write on Scotland's tramways. He was also interested in steam road locomotives and purchased one to prevent it being scrapped, donating it to a society in Glasgow.

He was looked upon as an eccentric recluse, having a habit of carefully picking through rubbish at jumble sales, or frantically riding his bicycle to scrapyards or derelict industrial sites in search of targets for his 'Box Brownie' camera. He also economised in his writing materials, scribing his letters on any scrap of paper including gas or electricity bills (examples in the Gallery). However, he was described by those who knew him as a "very clever" and "very gifted man". He had a quiet nature but when it came to dealing with the incompetence of government engineers and the destruction following the Beeching report he was voluble and biting in his criticism.

His book contains several data errors, but this is not surprising as it is a lengthy and highly-detailed work and he didn't enjoy the modern benefit of computer systems for recording, correlating and reviewing. The structure of the book and his style of writing can make it difficult for the general reader to follow, however this remains a reference work of the highest order, supplemented only by Peter Tatlow's book "Railway Breakdown Cranes" which was published almost 40 years later and approaches the subject from a different perspective.

John Brownlie, third from left, at Eastfield MPD, Glasgow, on 8th April 1950

Source of photographs and certain information above:

Ron Glendenning (UK) and Bruce Ward (AUS)

A Rapier Apprentice Abroad

BDCA member Tony Worman recalls his exchange visit to Hamburg as a Ransomes & Rapier apprentice...In 1956, partway through my mechanical engineering training, 'Rapier' (as R&R was always referred to, in the company and in the town) decided to instigate a new type of apprentice, that of ‘student apprentice’. I have no idea who thought up this ill-considered scheme but it did not last long. However, I was one of about twenty or so lucky lads chosen as the initial intake. We were provided with a room where it was intended we would gather to be given special talks, have discussions and study models, leaflets and engineering equipment.

During the second (and last) meeting it was announced that there was to be a general knowledge quiz, which was to be marked; the top four apprentices would be sent to Germany in exchange for four German apprentices. Two of us would be sent to Menck & Hambrock in Hamburg and the others to Demag in Munich. Luckily for me, part of the quiz required us to provide a list of words with their meaning. I recognised the Latin roots of many words, having learnt the subject at school, and my correct answers boosted my score; the first and last time that Latin ever came to my aid. My best mate Eddy and I were to visit Hamburg!

Menck & Hambrock manufactured a range of construction plant that was very similar to Rapier's, e.g. crawler cranes and excavators. They also made bulldozers and steam and diesel pile drivers. The family run company was established in 1868 (Rapier in 1869) and had a reputation for providing high quality and innovative equipment. I have no idea what they made during WW2 but I suspect tanks (their internet history pulls a discrete veil over the subject), but after 1945 they were at risk of having all their machine tools taken by the Allies as reparations for the materiel losses inflicted on the Allies by the war – Hamburg was in the British Sector.

Before leaving for Germany, I was told that Sir Richard Stokes, managing director of Ransomes & Rapier and Labour MP for Ipswich, advocated after the war that it would be a huge mistake to strip Germany of the means of reconstructing their cities and infrastructure. He believed that it was important to provide employment, wages, and goods to return life to normal peacetime ways as quickly as possible. His interventions established a friendly relationship with the two German companies and it was agreed that apprentice exchanges were a good means of instituting a greater understanding between the young people of the two countries.

So it came about that in August 1956, aged 19 years, in some trepidation, we reported to Menck’s head offices and were handed over to the works management to begin five weeks of training with a German twist. Most of the time we were expected to observe only - maybe they considered that English workmanship was a bit suspect - which after a while became a bit tedious. From our first meeting with the Herr Foreman - no doubt an ex Oberfeldwebel in the Wehrmacht - it was obvious that the military mentality of the workers was still ingrained in their psyche; we were expected to stand to attention when speaking to “management” and give very respectful answers to questions and instructions. Needless to say they soon found out that the English lads had other ideas about such matters that I am sure did not particularly endear themselves to the supervisors! A respectful smile when talking soon melted their hearts and we were sent off with a metaphorical kick in the rear.

Menck had three factories in Altona, a suburb of Hamburg, all within easy walking distance from each other. We were eventually given the freedom to visit them as and when we liked (did they want to get rid of us?). We soon found all the bars along the roads for a quick, small, glass of the local brew, of course only to withstand the hot summer days we always had then.

Their canteen served pretty grim food; mostly fatty boiled pork or gristly sausages accompanied by boiled potatoes and boiled cauliflower or red cabbage but no gravy. Yes, I know that food was still not plentiful and life was still pretty basic for the average person, but it was more than I could stand. After all I had got used to the delights of rabbit, whale, goat and spam spiced with Oxo during the war. When walking, we passed little cafés serving slightly more palatable lunches, though the cost of these soon ate into our daily allowances and lead to us successfully pleading for more money.

We were allocated digs in local family homes; Eddy to a very nice couple where the husband was a retired judge and I to an elderly and charming couple who spoke not a word of English. The husband was an inspector with the Hamburg trams. They had a first floor flat overlooking the entrance to Altona tram terminal. In fact my room was directly over it and I could clearly hear the familiar clanking of a tram, operating from crack of dawn to very late in the evening, but youngsters can always sleep on a telegraph pole without waking.

My Herr had been conscripted into the army at the age of about fifty and, during the last days of the war, was given a rifle and told to fight the Tommys or else we would slaughter all. He soon ended up in a British prisoner of war camp where he was, much to the surprise of all, very well treated. He resolved that after the war he would get to know the English better and hence the decision to take in one of us each year. Frau was a very nice mother hen who made sure I was well fed and washed.

I had been put into their twenty-five year old daughter’s room. Fraulein had been allocated the settee in the lounge but in reality we hardly ever saw her as she stayed with her boyfriend and they roared around Hamburg in his new Karmann Ghia sports car. I had my suspicions that he was somehow involved in the black-market to have then afforded such a machine. Fraulein worked in the main offices at Menck and spoke perfect English. During her infrequent visits I took the opportunity to unscramble the many misunderstandings that had occurred between her parents and me.

My first problem was at dinner on the first night. I had taken a small piece of some of the vilest smelling cheese that I was barely able to finish. Seeing my plate empty, Frau leans over and plops a very large piece on my plate. Despite washing my hands frequently I couldn’t get rid of that smell and even had to sleep with my hands held rigidly alongside my body. Kind soul, she even put some in my lunch time sandwiches.

I usually had lunch with the whole family on a Sunday and you can guess the menu - yes, as at the canteen but much better quality. Otherwise the food was very good, plentiful though of limited variety. Bear in mind that I visited Germany only ten years after the end of WW2 and their people had come through a period of huge food shortages and strict rationing until the German Government abolished all rationing in mid-1948. The German government relied on price and lack of cash to do all the rationing. In the UK, we continued with rationing of some foods until mid-1954!

Without doubt the Hamburg Germans I saw did work harder but there was one overriding incentive to do so - competition for jobs. Post-war Hamburg had been flooded by refugees from the Russian Sector of East Germany; said at the time to be up to one million people, all looking for jobs, a roof and a crust. Their hours of work were similar to ours but no tea breaks!

Hamburg’s industry, docks and shipbuilding yards attracted massive bombing raids by the Americans during the day and the RAF at night. One raid over three days in July 1943 comprised nearly 800 bombers and resulted in immense destruction to the city and the death of nearly 45,000 people. This raid unexpectedly created gigantic firestorms, which literally sucked oxygen from un-bombed adjacent areas causing asphyxiation of all living creatures. During my visit I was taken by friends on a tour of residential areas of the city that had been completely cleared of all rubble of bomb damaged buildings, and all that was visible, for as far as one could see, were the bare foundations of the buildings criss-crossed by the original road network. A wasteland where nothing moved.

We quickly made good friends with our work mates and never once heard any unpleasant reactions to our presence; unlike our mates who had gone to Munich. Hamburg’s Scandinavian neighbours had always influenced their Germanic attitudes, in contrast to Munich that had once been the heart of Nazism.

One good friend, Uwe, invited us to meet his parents and girlfriend during one Sunday lunch. We had an enjoyable meal with a very pleasant group of people with good, easy conversation. After the meal we all sat in the lounge where several large photo albums were brought out containing pre-war photos of Hitler and his entourage. Many of these photos I have never seen before or since. The parents tried to convince us, during long discussion, that Hitler had been good for the Germans up to the war by his handling of the economy.

The discussions were a great embarrassment to us both, particularly as guests in a private house; we found it difficult to put up a strong defence of our views of the whole period. We did not fall out with Uwe or his girl, in fact they took us out the following Sunday to inspect the East German (Russian) border via Luneburg Heath. The high fence with its frequent watchtowers was a part of the Iron Curtain and ran for as far as the eyes could see; north to the Baltic Sea and south towards Berlin. A very threatening and awe-inspiring sight that put the fear of God in me – thank goodness we had the atomic bomb at the end of the war.

Hamburg had good nightlife but not for a poor apprentice with hardly enough money to survive. We were there too early to see the Beatles who worked in Hamburg in 1961!

On our return to England I had to write a report on my experiences and views on the visit; I rather think mine may have had a very restricted circulation, as I did not pull any punches. Some of my comments were:

- A large percentage of Menck’s machine tools were very modern; those of Rapier were mostly pre WW2, some pre WW1 and others even Victorian.

- I never saw a shaft fixed by a taper key; all had splined ends that were machined using fully-automated machine tools. Assembly in the fitting shops was very fast.

- One operator frequently supervised up to six machine tools; in Rapier one man never operated more than one machine tool.

- Cast bearing and other housings were very clean and modern in appearance. Maybe not as economical to make as ours because occasionally more patterns/cores were needed.

- Most of the equipment manufactured had very modern and appealing lines. Ours were old designs and had hard bolted/riveted corners.

- The Apprentice Training Centre was far larger than ours (for a similar size of company) with modern machine tools, classrooms, and a drawing office for about a dozen apprentices. Our machine tools were throw-outs from the machine shop and had a mind of their own when operated.

- Apprentices trained for only three years, with nearly all the time spent in the training centre.

- The Germans worked harder, or least the ones I saw working.

- There were girl apprentices in the training centre, though never seen in the workshops where we were placed! Did “Tommys” have a certain reputation?

Well, they sent us to learn how the other side did things and we certainly learnt a lot. And did the visit meet the 'mutual understanding' expectations of Richard Stokes? I think so.

© A.R.G. Worman 2011

The Breakdown Train

By E. S. ValentineReprinted from The Strand Magazine Vol. XXI No. 28 (1901)

THE BREAKDOWN TRAIN

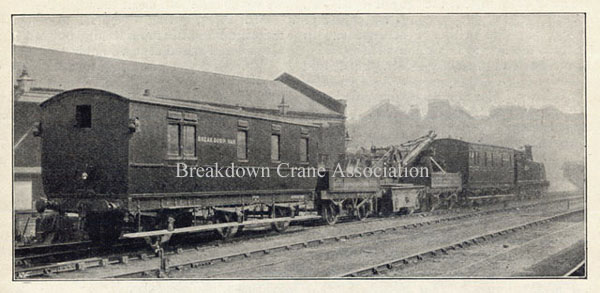

UPON the great highways of transit in this kingdom, and indeed upon every railway in the world, there runs from time to time a train which takes precedence of all other trains. Everything – even the Royal express – must give way to it, for without it, in the peculiar emergency by which it is called forth, all on the line would be chaos and confusion. It is called the Breakdown Train (or Wrecking Train), and it runs between its own head-quarters and the scene of an accident on the line. It is a combination of travelling workshop, store, and magazine of tools, as well as a travelling ambulance capable of affording first aid to the injured.

In this era of universal railway travelling a breakdown on a busy railway is little short of a public calamity, even though unaccompanied by serious loss of life and property. To the breakdown train belongs the function of repairing the calamity; it speeds to the rescue; every engine, every carriage, every truck, every item of rolling-stock is shunted to let it pass, because each minute that it is delayed adds to the twin streams of pent-up traffic which is disorganizing the railway.

In order to gain a glimpse of the working of the breakdown train let us suppose that one dark, stormy night there flashes into a large passenger station such a message as this :–

"Serious accident at Stark Junction. Locomotive 45 and five carriages down the embankment. Numerous passengers."

Two copies of this telegram are instantly sent, one to the locomotive superintendent or his foreman in charge of the "locomotive shed," and the other to the "traffic inspector" of the district. To the locomotive department of every large station are attached a breakdown train and gang, which are maintained in a constant state of efficiency. Provision is made for action at the briefest notice, day or night. A list of the names and addresses of the foreman in charge of the breakdown vans and of the skilled men, twelve in all, who constitute the breakdown staff, hangs up, framed and glazed, on the wall of the office. If a larger force is thought necessary it is made up from the ordinary staff connected with the locomotive department.

In a few minutes the men are summoned from their beds, and are seen hurrying towards the van, dressing as they run. The breakdown train is already prepared for the journey. Sometimes it consists of seven vehicles, but never under five, the fewer the better so long as it is replete with equipments. In the former case the train is made up of two tool-vans, one riding-van, one laden with wood "packing", the breakdown crane, and two "runners" or waggons which are employed to protect each extremity of the crane, one supporting the "jib", while the other is burdened with the "balance-blocks".

THE RIDING-VAN

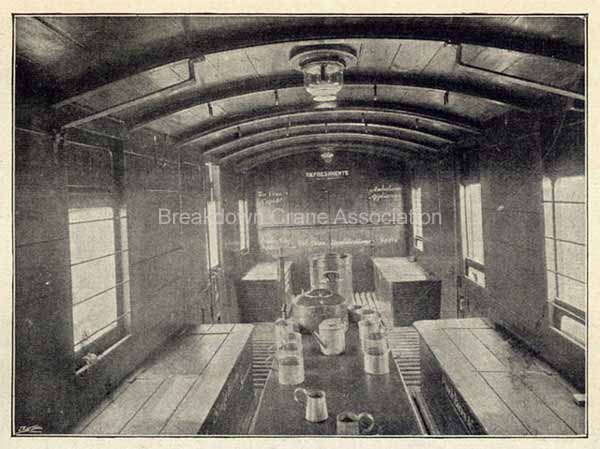

And now to the rescue! We are already at full speed down the line, and the riding-van, wherein the wreckmen are congregated sipping coffee, presents an animated scene. In a corner sits a young surgeon drinking coffee with the rest, and discussing with the foreman the probable cause of the accident, whose character can as yet only be approximated from the brief despatch in the foreman's hands. In the old days the breakdown gang had no riding-van; they had to ride on the trucks or on the engine or hang on how and where they could. The present van is capable of holding forty men. One end is fitted with cupboards, which when opened disclose flags, fog-signals, signal and roof lamps used for lighting and protecting the train, as well as train signal-lamps, ready trimmed for lighting, and four train-lamps. A stove occupies the centre of the van, to which an oven is attached, so that, if necessary, the men may cook their food. "Box-seats" are constructed around the sides of the riding-van, which serve as receptacles for various tools, such as wood "scotches", small "packing shovels", hammers, bars of many kinds, and a large variety of what our mentor describes as "sets."

This "set" plays a very important part in the labour of clearing the line or rescuing imprisoned victims of a railway disaster. It is used for cutting shackles or bolts, and is a piece of sharpened steel resembling the head of an axe without the handle, from one to three pounds in weight. A piece of hazel, commonly called a "set-rod", is wrapped round it, and the two ends form the handle. The set is held on anything which it is required to cut, and with the blows of a heavy hammer in the hands of those accustomed to such work it will quickly sever any bolt or shackle.

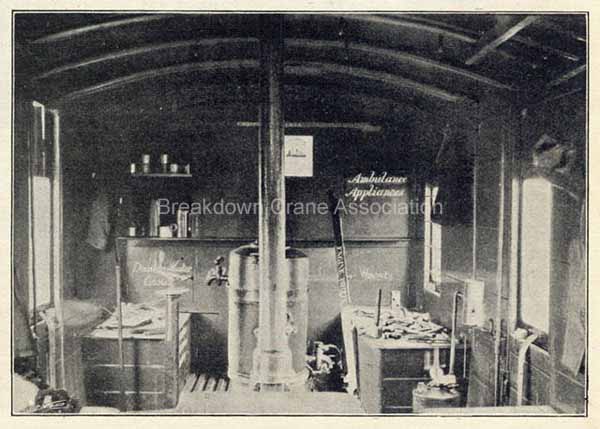

Shovels, hammers, chisels, bars, and other implements are also ready to hand in this van. One cupboard contains the handlamps needed by the official staff, each lamp having the name or the initials painted thereon. Still another cupboard is labelled "Ambulance". The foreman opens the doors and reveals two tourniquets, half-a-dozen compressor bandages, scissors, forceps, adhesive plaster, lint for dressing, splints for broken limbs, antiseptic fluids, sal volatile, needles, sponges, basins, while an ambulance-stretcher is folded away in one of the lockers.

THE RIDING-VAN – AMBULANCE SECTION

Another locker contains the necessary food and provisions, bread, butter, tea, coffee, sugar, and last, but not least, tobacco. This hasty inventory omits many articles of importance, but we must move rapidly on to the next van, merely noting the curious fact that the greater number of the tools which have handles are painted a bright vermilion, so as to be easily distinguishable in the dark or in the confusion which attends a wreck on the line.

By the light of a powerful lantern we examine the tool-van, passing through, in order to do so, a small compartment at the end of the riding-van, which forms a great contrast to the body of the vehicle. It is reserved for the directors or officials of the road who may wish to proceed to the scene of the breakdown, but at present it is devoid of occupants, owing to the lateness, or rather earliness, of the hour. The breakdown train cannot stop even for a director, but officials have often been known to leap aboard at the last moment on the occasion of some important mishap.

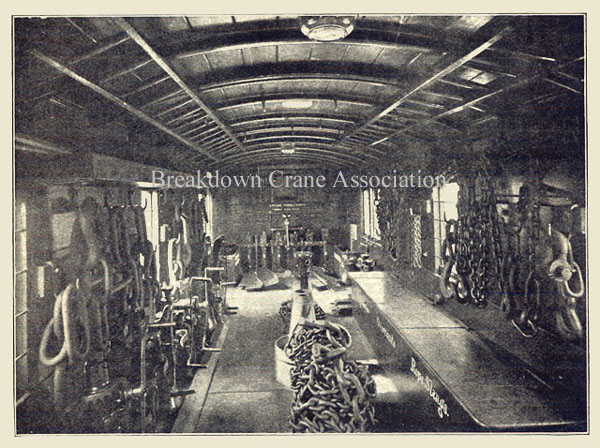

INSIDE THE TOOL-VAN

The tool-van glitters and bristles like an armoury. The floor is divided into little streets and squares, as may be seen by the accompanying illustration, formed by rows of jacks, ramps, and pyramids of chains, each placed with due regard to neatness and to prevent confusion and intermingling. The upper portion of the sides of the van is looped around with strong cables of rope or chain for haulage purposes, and is also arranged and fastened with occasional lashings to be easily loosened ready for use.

A couple of sets of strong ladders are lashed to the roof. These are fitted with socket ends, and when, in event of a collision, waggons are piled up to a height of twenty or thirty feet, they are of the utmost service in scaling the wreck. The lower sides of the van are devoted to an array of single and double hooks, and huge iron loops for the jacks. The remaining space in the van is filled up by bars, levers, and other appliances, all arranged in an orderly fashion. Order seems to be the guiding motto in the breakdown train. There are in this van no lockers, for the reason, as your guide informs you, miscellaneous articles get out of ken when hurriedly thrown in, and are afterwards urgently needed. At one end of the van there is an 8in. vice, secured to a bench, specially constructed, so as to be portable if required; and a tool-rack, containing files, chisels, and hammers, every article being within easy reach. Before taking leave of this section of the breakdown train let us not fail to notice the hue of the paint on the inside of the van. It is a clear white, the object being to throw every article into greater relief, for every jack, every lever or wrench, is painted of a ruddy vermilion. The object is, of course, to indicate its locality when in a half-buried state. Otherwise after the confusion and strenuous toil of a breakdown, especially at night, a number of the tools would be lost or mislaid.

The next vehicle carries the 15-ton steam crane with which, at some point or other, most railways in this country are now equipped, although the hand-crane is more generally employed. A properly-designed breakdown crane is the most suitable, and probably the most powerful, appliance known for clearing away obstacles with dispatch. The crane may not be of more than six or eight tons' lifting capacity, but the class of lifting usually dealt with does not exceed this weight, 90 per cent. of the work on English railways being under five tons. The hand-cranes are simply constructed with single and double motions, jibs capable of elevation to a moderate extent, and with a radius of about 20ft.

The many purposes to which they can be so readily applied render them, within their own limits, more popular than the larger cranes. The balance-box of the crane is movable, and when in use is heavily weighted with a number of blocks of cast-iron. In addition to this, when a heavy weight is being raised, the crane is secured to the permanent way by means of four clips, which are attached to each corner of the crane and clip the head of the rails. The crane itself is commonly worked by five men. The frame of the crane is iron, and the waggon which supports it is also of iron, weighing altogether from fifteen to thirty tons. Next to the crane is another runner on which rests the jib of the crane. The latest form of the crane is a combination with the locomotive, such as is in use by the North London Railway.

Having thus described, in a somewhat imperfect fashion, the breakdown train and its principal contents, let us hasten on to the scene of the disaster. The waving of red lanterns and the explosion of fog-signals apprise us that we are approaching the fatal spot. Scarcely has the riding-van sufficiently diminished its speed than, lanterns and torches in hand, the breakdown gang is swarming along the metals, the foreman at their head. This personage, who is also an official of the line, is a heavy-set, intelligent man of fifty. In railway circles he is credited with being a specialist in breakdowns, and to his ingenuity and skill are due many of the technical improvements which have in recent years marked this important branch of the service. Whether the accident be a collision, a derailment, or due to damaged machinery, however dense the wreckage or appalling the results, he is said never to lose his head or fail to accurately gauge the disaster, and instantly sets to work to apply a remedy. "Nothing", he remarks, "is so requisite as a cool head". His first idea is to clear one road; he attacks with discretion at one point to ease another.

We will pass over the pitiful human details of the accident which has occurred. It will be enough to say that in the present instance a locomotive and five carriages have plunged headlong down a steep bank, leaving three other carriages derailed close to the main line. The blackness of the night, the howling of the tempest mingling with the groans of the wounded and dying, the shouts of the workmen, the dark forms rushing hither and thither, women wringing their hands in an agony of supplication for help to those who are unable to render any – this is but a rough picture familiar to the average breakdown gang. With their advent come lights; flaming, spluttering torches are set up on the summit of the débris.

A number of the wreckmen immediately attack the work of extricating the survivors from the wreck, while others bend their trained energies to the clearing of the line. The foreman makes room to get his crane, jacks, and ramps at work. In event of a collision he makes huge bonfires of the matchwood; some of the crippled waggons he replaces on the line, bandaging them together to make them fit for travel. Such vehicles as can no longer travel he pitches to one side to deal with them at a more convenient time. If the waggon has become partially embedded he raises it by means of the jack; and if not too far distant from the rails replaces it by means of the ramp. In such manner does the master railway wreckman fight and bore his way through the outer mass of ruin until he reaches the heart of the difficulty, sparing neither himself nor his men until the line is clear.

The breakdown gang is under his sole charge, and he will brook interference from no one, and rightly so. With more than one person giving orders, confusion becomes worse confounded, and grave risk is run of adding to the effects of the disaster by killing or maiming some of the breakdown staff, whose work, as it is, is often of a sufficiently dangerous character. As an instance of this, some years ago, while one goods train was running over a junction, the driver of another goods train, approaching the same junction from the other line, ran past the distant and home signals set to protect the first train, cutting right through the latter. Waggons from both trains – overturned, upturned, on their sides, mounted upon one another – lay in a great heap, blocking all lines. As a preliminary step the foreman decided to pull the heap apart. While he was getting the engine in position and having his favourite hauling-chain affixed thereto he directed two of his gang to go in amongst the waggons and undo any couplings they could find. The men crawled in out of sight; but no sooner was the chain fixed than someone (not the foreman, you may be sure) told the driver to go ahead. The men inside heard the order given, and shouted out in terror, "Let us get out of this first". The order to the driver was, of course, promptly countermanded, or the two men would have stood little chance among the plunging waggons and the crashing timber when once the engine began to pull on the hauling chain.

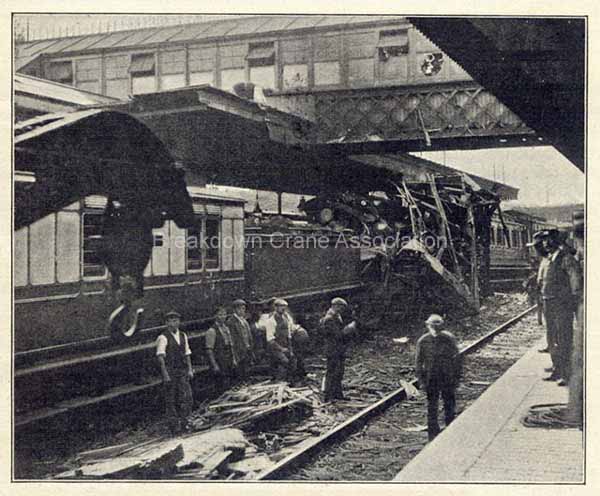

THE BREAKDOWN GANG AT WORK AFTER THE SLOUGH ACCIDENT

It is wonderful to observe the special faculties developed by the expert. At a single glance the expert in railway breakdowns recognises precisely what tools or appliances will be required in the case of each defaulting vehicle. There were said to have been experts in the old coaching days, before the advent of railways, whom a "spill on the road" made masters of the situation. A certain coachman, in the early days of steam locomotion, is said to have thus drawn the line between coach and railway accidents. "It is this way, sir," said he. "If a coach goes over and spills you in the road, why there you are! But if you goes and gets blown up by an engine – where are you? ". And occasionally there are accidents so disastrous in their results as almost to baffle the eye even of the expert, and make it puzzling to know how to begin to extricate order out of chaos.

In the present instance, however, after the work of rescuing life and limb from the carriages which have been precipitated down the embankment, putting out the engine fires, and removing the glass and splinters, for every window-pane has been broken, the duties of the wreckmen are immediately concerned in replacing the three derailed vehicles on the line. A screw-jack is employed to lift up the end of each waggon separately, after which the principal implement is the ramp. The ramp is constructed to fit the rail at one end and the sleeper at the other. It has two spikes or claws at the end which is affixed to the sleeper, which are immediately in front of the wheel of the waggon which it is intended to replace on the rails. Either two or four of these ramps can be used at the same time for a waggon, according as may best suit its position on the road. As soon as the weight of the carriage gets upon the lower end of the ramp it presses the teeth into the sleeper and so compels it to keep its position.

If the waggon has overturned the "snatch-block" is the most useful appliance. A third implement is the "clip", which fits on the rail. The rail, indeed, is the great fulcrum and base for the operations. The waggons and engine at the base of the embankment are pulled back to the line by means of two snatch-blocks, one secured to the waggon and the other fastened to the draw-bar of the crane, which is firmly secured to the rails. The rope passing through both blocks draws the waggon within reach of the jib of the crane, which takes the waggon up bodily and places it on the rails.

In all this work, varied and intricate, laborious and often exciting, each master wreckman has his favourite appliances, jacks, hauling-chains, ropes, etc., whose special virtues he extols, often at the expense of the apparatus in use on rival lines. But however it is done, the line, in nearly all wrecking cases, is cleared in what seems to an outsider an incredibly short space of time. The traffic is resumed; day breaks upon a peaceful landscape. We revisit the scene of last night's disaster, but the rays of the morning sun reveal no indication of anything unusual having occurred. Of the wreck, ruin, and confusion not a trace now is to be seen, so thoroughly have the wreckmen accomplished their task. The huge engines pitched over like child's toys, their plates rent and torn asunder, revealing the very bowels of each iron monster; carriages reduced to flimsy matchwood, weakly strung upon a quivering metal harness; twisted ironwork and bent axles – of all this and more, if there has been a collision of the "telescope" variety, there remains now only the recollection.

The valiant breakdown gang has gone home to bed, after a hard night's work. In winter each member of the gang dons a top-coat provided by the company, and in addition to "what time they may make" a bonus of two shillings is given to each on every occasion he is called upon to perform "main line breakdown work."

Some singular accidents occur from time to time, but railway history repeats itself, and each extraordinary mishap serves as a precedent, and furnishes its own moral to the professional wreckman. For example, a few years ago at Kelthorpe sidings two engines collided, and became so involved and wedged together that it required the strength of two others of even greater strength and size to pull them apart. The Farlingham Tunnel was once blocked up from rail to roof by a collision. While trying to find a path through the wreckage the foreman and several of the breakdown gang were nearly choked with pepper. It appeared that this condiment had been spilt from the broken casks which held it, until it lay ankle deep on top of the débris, like snow crowning an Alpine summit.

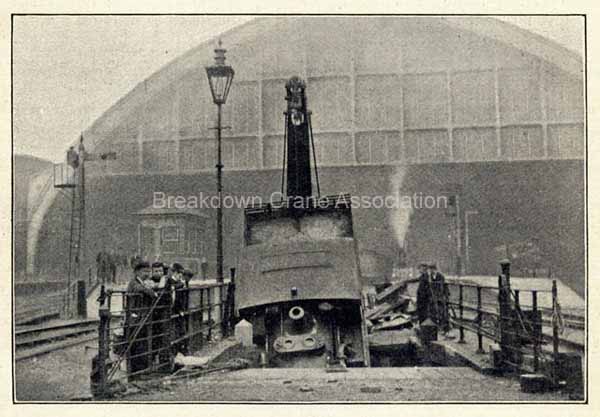

A curious accident, and one not easy to manage, happened two or three years ago right before the eyes, so to speak, of the breakdown gang. A large locomotive at St. Pancras suddenly took it into its head to plunge down a lift-way into an adjacent subterranean workshop. It was, in the strictest sense, a clean dive, and there the locomotive lay, literally wriggling on its buffer, until the breakdown gang, with the aid of their steam cranes, hauled it out hind-foremost.

RAISING AN ENGINE WHICH HAD PLUNGED THROUGH A LIFT-WAY

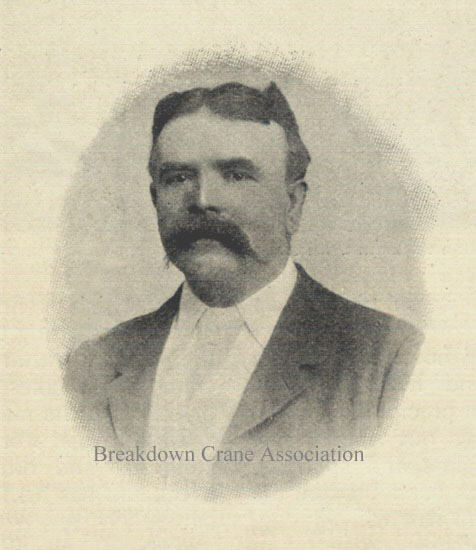

From America the most astonishing and appalling accidents are constantly reported. In that country of magnificent distances the wrecking train plays an even more important part than it does with us. But the work is the same; and in their appliances and equipments they differ but little from us. And it is doubtful if they have on any of their railways a man of greater ability and experience than Mr. Weatherburn, of the Midland Railway, to mention only one of the veterans of whom our railway system may well be proud.

In conclusion it may be remarked that the crew of the wrecking train bear a close analogy to our firemen on land and the lifeboatmen of our coasts.

It is, in brief, the Railway Salvage Corps; upon its courage, industry, celerity, and judgment depend not only human life and property, but the free current of commerce and business communication in which millions of money may be, and often are, closely involved.

MR. ROBERT WEATHERBURN, HEAD OF THE BREAKDOWN DEPARTMENT OF THE MIDLAND RAILWAY

From a Photo. by Arthur Weston